Richard Wagner

Tannhäuser, Lohengrin, and Die Meistersinger

Born: 22 May 1813 in Leipzig

Died: 13 February 1883 in Venice

{Life} {Music} {Tannhäuser} {Lohengrin} {Die Meistersinger} {A Personal Note—Bayreuth}

Life

Wagner is a great example of the fact that someone can write incredible music, or be a phenomenal artist, or dazzle the world with unforgettable words, and still be a not-very-nice human being. Yet if we restricted our listening and performance to the music of those whose lives we sanctioned, we would have a very short list of pieces to enjoy. So try to separate Wagner the person (not especially admirable), and the uses to which his music was once put (revolting), from his unique artistic achievement (amazing).

Passionate about music, and especially opera, from an early age, Wagner began his career as chorus master in the Würzburg opera. Here he completed his first dramatic work, the German Romantic opera Die Feen (The Fairies), on a story by the 18th-century Italian playwright Carlo Gozzi (better-known works to draw on Gozzi include Puccini’s Turandot and Prokofiev’s Love for Three Oranges). Wagner wrote his own libretto for Die Feen, as he was to do for all of his works. He probably wins the prize for the composer who wrote the most prose works as well. His collected writings, which include his self-serving autobiography Mein Leben (My Life), fill many volumes, and he never hesitated to put in writing his (very strong) opinions.

Wagner’s second opera, Die Liebesverbot (Forbidden Love) was based on Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure (the 19th century was crazy about Shakespeare); his third, Rienzi, was a five-act grand opera based on a contemporary novel about the Roman demagogue. The overture, which is quite nice, is still performed.

By this time Wagner’s life was beginning to resemble an elaborate opera plot on its own, and for decades thereafter it could accurately be described as a hot mess. He was music director first of a traveling opera company and then the theater in Riga; his marriage to an opera singer at the age of 23 rapidly degenerated into infidelity; he fell into debt, had his passport impounded, and had to sneak out of Riga; he lived the life of a starving artist in Paris for several years and scraped together a living through journalism and by making commercial arrangements of opera excerpts; he was threatened with debtor’s prison. A period in Dresden as Kapellmeister for the King of Saxony ended badly; caught up in the revolutionary fervor sweeping Europe in 1848/1849 (he knew the Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin), he had to flee for his life, hide with Liszt in Weimar, and finally sneak into neutral Switzerland on a false passport, where he remained under police surveillance for some time.

In Switzerland Wagner was based in Zürich, where he wrote a series of major prose works outlining his artistic philosophy: Die Kunst und die Revolution (Art and Revolution, 1849), Das Kunstwerk der Zukunft (The Artwork of the Future, 1849), and Oper und Drama (Opera and Drama, 1850–1851), as well as the stridently anti-semitic Das Judentum in der Musik (Jews in Music, 1850). One of the most important concepts elaborated in these writings is that of Gesamtkunstwerk, “total art work,” where all of the arts work together to create a unified entity—music, poetry, dance, architecture, painting, sculpture—with theaters specially built for the best performance conditions. Texts should use Stabreim (“stem rhyme”), which emphasizes alliteration, and melodic motives (what we now call Leitmotifs, “leading motives;” Wagner never used the term) will recall and foreshadow important ideas. Ensembles and choruses, unnatural to drama (unlike, say, singing), will have no place.

During his time in Switzerland and afterwards, Wagner repeatedly pulled off the neat trick of convincing other people to support him financially. One of the most famous of these suckers, I mean benefactors, was wealthy businessman Otto Wesendonck, whose generosity Wagner rewarded by falling in love with his wife. But at least the artistic results were worth something: the gorgeous group of songs set to Mathilde Wesendonck’s poetry (the “Wesendonck Lieder”) and, ultimately, Tristan und Isolde, Wagner’s operatic homage to that classic illicit love story and his own desire.

Another very famous patron was the young Ludwig II, King of Bavaria, who took over Wagner’s massive debts, provided a house for him in Munich, arranged for performances of his operas, and in general functioned as his sugar daddy for almost two decades. Ludwig’s passion for Wagner’s operas manifested itself in other, very visible ways. One of several residences the King built, Linderhof, contained an elaborate grotto that could be lit in red to represent the Grotto of Venus in the Hörselberg, where Tannhäuser dallies with Venus in Wagner’s eponymous opera. Nearby was Hunding’s Hut, a log cabin built to mimic the Act I set of Wagner’s Die Walküre, as well as a hermitage meant to represent the hermitage of Gurnemanz in Act III of Wagner’s last opera, Parsifal. Most spectacular of all, though, was the faux-medieval castle Neuschwanstein, literal poster child for German tourism and the model for the iconic Disney castle. Never completed and never lived in by Ludwig, its Gothic revival style matches the time period of almost all Wagner’s operas, and it is decorated throughout with scenes from Wagner’s operas. The elaborate Minstrels’ Hall was inspired by the same in the Wartburg, the setting of the singing contest in Tannhäuser. For fans of Wagner, the castle is a real treat. And if you go there in deep winter, as I did, you will be spared the tourist hordes and rewarded by snow-covered enchantment.

By the time Ludwig initiated his Über-patronage, Wagner had embarked on a new and more lasting love affair than anything he had experienced previously. While Hans von Bülow, one of the leading conductors of the day, was preparing the Munich premiere of Tristan und Isolde, Wagner was busy sleeping with his wife, Cosima. She happened to be Liszt’s daughter, and her dad was not exactly thrilled with this liaison. His reaction was a bit rich, though, given his own list of dalliances. Cosima, in fact, was his illegitimate daughter by a married woman.

Cosima and Wagner soon moved in together and lived, more or less, happily ever after. Their three children, all born before their parents wed, were (I am sorry to say) named after characters in Wagner’s operas—first Isolde, then Eva (the heroine of Die Meistersinger) and finally Siegfried (hero of the Ring Cycle). It was for Cosima’s birthday (always celebrated on Christmas Day) in 1870 that Wagner wrote the charming Siegfried Idyll, which includes music from that opera.

Wagner’s vision of a theater to match his performance ideals was finally met with the construction of the Festspielhaus in Bayreuth; its innovative design conceals the orchestra while still enabling it to be heard fully. It remains a pilgrimage site for true believers (the seats are famously uncomfortable) with its dedication to Wagner’s works. Wagner also moved to Bayreuth to live; his home Wahnfried (“peaceful folly”) is now a museum. He died not there, however, but during a stay in Venice.

Music

Wagner’s first three operas are not (and have never been) part of the general operatic repertoire. The ten he wrote after that are very much part of the standard repertoire, making Wagner one of the big five in the land of opera (the others being Mozart, Verdi, Puccini, and Strauss). The ten operas, most of which are extremely long, are Der fliegende Holländer (The Flying Dutchman, based on an ancient legend in the retelling by Heinrich Heine); Tannhäuser (based on the medieval Minnesinger); Lohengrin (based on the medieval legend); Der Ring des Nibelungen (the Ring of the Nibelung, based on the medieval epic), also known as the Ring Cycle, which consists of four separate operas that represent the concept of three acts and a prelude: Das Rheingold (The Rhine Gold), Die Walküre (The Valkyrie), Siegfried, and Götterdämmerung (The Twilight of the Gods); Tristan und Isolde (based on the medieval epic); Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (The Mastersingers of Nuremberg, based on the 16th-century Meistersinger Hans Sachs and his cronies), and Parsifal (based on the medieval epic). Just in case you were wondering, Wagner was obsessed with the Middle Ages, but so was pretty much everyone else in the nineteenth century (see: Neuschwanstein). A frequent theme is redemption through love, or more specifically the redemption of the hero through the unquestioning love of a woman (no wishful thinking there, not at all).

Thanks to his philosophical ruminations on the goals and structure of opera, Wagner’s style gradually changed (although he occasionally reverted to earlier practices; e.g. Parsifal uses both a male chorus—the Knights of the Holy Grail—and a female chorus, the Flower Maidens). The term “opera” was rejected in favor of the designation “music drama.” The Overture gave way to the Vorspiel (Prelude). The organization moved away from the set numbers of traditional opera and Wagner’s own early works—aria, recitative, ensemble, chorus, etc.—to a continuous through-composed structure, an innovation that soon marked virtually all of opera. Wagner’s melodic style changed as well, going from vocal lines with regular periodic phrases to a fluid arioso style of “endless melody” that carefully followed word stress. The voice itself was treated at times as simply another instrument, but it had to be huge to be heard above the expanded orchestra Wagner favored. Indeed, the specific type of tenor Wagner’s works require is known as the Heldentenor, “hero tenor,” for its demands on the singer. Pity the poor Siegfried, for example, who is onstage throughout almost all of his opera. That work ends in a glorious duet with Brunnhilde, but the soprano, who appears only in this final scene, is vocally fresh, whereas the exhausted tenor... Wagner finally caught on to the fact that singers, too, are human, and paced his soloists more reasonably in Parsifal.

Wagner was also an innovator with the orchestra. Der fliegende Holländer uses a wind machine; bells for the Holy Grail play an important role in Parsifal; the descent into Niebelheim in Das Rheingold is marked by 18 anvils. New instruments were required for the Ring: an alto oboe, a bass trumpet, a contrabass trombone. Most famous are the so-called “Wagner tubas,” played by horn players and intended to fill the aural gap between the French horn and the trombone.

We’ve already mentioned the Leitmotif, the short motive open to endlessly varied transformation on its return appearances. By the time we get to the Ring Cycle, they form a rich orchestral web that provides an unspoken commentary on the drama, a musical stream of consciousness underlying the sung text. Even more important than the Leitmotif, however, is Wagner’s use of harmony, which changed the language of music forever. The use of chromatic harmonies, sequential variation, diminished seventh chords (which can resolve four ways, of course), suspensions, unresolved dissonances, and constant modulation all worked to create an incredible and incredibly powerful harmonic tension. Nowhere is this more evident than in Tristan und Isolde, whose famous dissonant “Tristan chord” when the Vorspiel has barely begun sets the tone for hours of harmonic yearning that exactly parallels the lovers’ own desire (“promised but evaded fulfillment”). It is a direct line from the chordal puzzles of Tristan to the atonality of the early twentieth century.

One of my professors in graduate school used to refer to Wagner as “King Richard,” and there’s no denying the massive influence he had on the nineteenth century and beyond, and not merely in the realm of music. Attempts to meet the staging demands of Wagner’s work, especially the Ring, led to numerous innovations in stagecraft. Writers such as Joyce, Woolf, Proust, D.H. Lawrence, and Thomas Mann are unthinkable without Wagner. Every cultured member of Western society knew of Wagner, most knew his music, and some knew it extremely well. It’s been said, in fact, that the three individuals about whom the most books are written are Jesus Christ, Napoleon, and Wagner. And, sadly, the enthusiastic embrace of Wagner’s music by Hitler and other Nazis (and the enthusiastic embrace of National Socialism by members of the Wagner family in turn) continues to taint our view of the composer.

On the positive side, Wagner has generated some excellent quotes: “Wagner has great moments but dull quarter hours” (Rossini); “One can’t judge Lohengrin after one hearing and I don’t intend to hear it a second time” (Saint-Saëns); “Wagner is a beautiful sunset mistaken for a dawn” (Debussy); “Wagner’s music is better than it sounds” (Mark Twain; someone also said “Puccini's music is not as good as it sounds,” but I have yet to identify the author). And as one wag put it, “Parsifal is like Götterdämmerung but without the funny bits.” (This is a joke. There’s nothing funny about Götterdämmerung).

Tannhäuser

Wagner began work on Tannhäuser in the summer of 1842, when he drafted the scenario in less than three weeks’ time (Wagner always wrote his own libretti). He began composition the following summer and finished in April 1845 (despite being an unpleasant person in many respects, Wagner is an excellent role model in finishing things even when they took a long time. In the most extreme example, 26 years elapsed between the prose scenario for the Ring in 1848 and completion of the four operas in 1874). Tannhäuser was the second of what Wagner called his three “romantic” operas, preceded by Der fliegende Höllander and followed by Lohengrin.

Tannhäuser premiered in Dresden, where Wagner was working for the King of Saxony, in October 1845. Not particularly successful at the start, it soon became rather popular in German opera houses. In 1860 Wagner received an invitation for a production in Paris and began revising it as needed, which means that his original 1845 music sometimes sits rather uneasily beside his much more modern style of fifteen years later. Act I received many changes, including an extended bacchanale. The Paris premiere in March 1861 was a huge scandal, however, and opposition from the powerful Jockey Club ended the opera’s run after a mere three performances.

What didn’t the Jockey Club like? Well, the club was a prestigious gathering of high society men; attendance at the opera was one of their many rituals. Arrival in time for the start of the opera was not, however, one of these, as Jockey Club members were still dining at that time. Instead, they showed up for the second act, which, in Paris, always included a ballet. This was the Jockey Club’s favorite part of any opera, as they got to ogle the dancers’ legs. Remember, we are in Victorian times here, when no “nice” woman ever showed her legs (referred to as “limbs”), and even legs of tables were covered by long heavy tablecloths. Yes, this is weird.

Wagner knew he had to include dance to get Tannhäuser performed in Paris, but he balked at a second-act ballet and instead expanded the bacchanale in Act I, where it fit nicely in terms of the drama. But Jockey Club members, absent for Act I and confronted instead with a dance-free Act II, revolted, effectively sealing Tannhäuser’s fate in Paris. It didn’t help that Wagner’s invitation had been arranged by Princess Pauline Metternich, loathed by members of the club (and many others). The Jockey Club still exists today, by the way, but I have no information about their opera-going habits.

Tannhäuser, Wolfram von Eschenbach, and Walther von der Vogelweide, characters in the opera, were all real people, active around 1300. Wolfram von Eschenbach is considered Germany’s greatest medieval poet and is author of the epic Parzifal, the source for Wagner’s last opera. Tannhäuser and Walther von der Vogelweide were both Minnesingers, medieval poet-musicians who frequently sang about love (“minne”). Walther von der Vogelweide was much more prolific, better-known, and more highly thought of than Tannhäuser, but it is Tannhäuser around whom a legend grew (by the fifteenth century at the latest) that has him frolicing on the Venusberg and then going on a pilgrimage to Rome to seek absolution from the pope. It is this legend, in various nineteenth-century versions, that Wagner drew on for his opera. The themes of sexual longing and redemption through the love of an unquestioning woman are, of course, favorites for Wagner.

The opera takes place in Thuringia in the first decade of the thirteenth century. The Paris version of the opera is outlined below.

ACT I

After the excellent overture, the curtain rises on the interior of the Venusberg (considered to be the Hörselberg, near Eisenach). Heinrich von Ofterdingen, known as Tannhäuser, is living here with Venus, goddess of love, after leaving the court of Hermann, Landgrave of Thuringia. Tannhäuser is asleep in Venus’s arms while the bacchanale goes on around them. At the conclusion of the bacchanale, Tannhäuser indicates that he is ready to return to the real world to seek salvation from the Virgin Mary (after he sings of the joys of Venus and carnal love). The Venusberg vanishes at the sound of Mary’s name (a rather tricky stage effect) and Tannhäuser finds himself in a valley by the Wartburg, the Landgrave’s castle. A band of pilgrims passes on their way to Rome, and Tannhäuser is overcome by penitence. The Landgrave and his knights come upon him as they return from a hunt, and urge him to rejoin them, which he does after Wolfram von Eschenbach intimates that Elisabeth, niece of the Landgrave, loves him.

ACT II opens with a terrific aria by Elisabeth, “Dich teure Halle,” in the Minstrels’ Hall in the Wartburg, where she expresses her joy that Tannhäuser is returning; she has avoided the Hall since he left. Tannhäuser enters with Wolfram von Eschenbach (who is also in love with Elisabeth). The reunion is followed (after a quick Landgrave/Elisabeth interaction) by the entrance of nobles and minstrels in preparation for the singing contest on the true nature of love; the winner will receive a prize from Elisabeth.

Wolfram sings on love as spiritual refreshment, to be kept pure; Tannhäuser counters with the importance of sensory pleasure (this becomes an ode to Venus). This is scandalous, and Tannhäuser is saved from a mob of angry knights by the intercession of Elisabeth. The Landgrave tells Tannhäuser to join the pilgrims and go to Rome to seek forgiveness.

ACT III begins with Elisabeth again, now outdoors praying at a shrine, and joined by Wolfram. The pilgrims return without Tannhäuser, and Elisabeth prays to be taken to heaven so that she can intercede directly for Tannhäuser. She then returns to the Wartburg, and Wolfram sings his famous “Hymn to the Evening Star.”

Tannhäuser shows up, in rags, looking for the way back to the Venusberg. Despite his penitence, the pope has refused absolution. “Fat chance,” said the Pope (in less modern terms, of course), “unless my papal staff sprouts leaves. Har har.” Venus appears and beckons Tannhäuser to join her, but Wolfram mentions Elisabeth’s name, at which point Venus vanishes. Knights now come down from the castle bearing Elisabeth’s corpse; Tannhäuser, dying, sinks down beside it, just as a fresh batch of pilgrims (that’s us, the chorus) appears, bearing the Pope’s staff, now covered in green shoots. Tannhäuser is redeemed, so there’s a happy ending after all, as our triumphant music and repeated “Hallelujahs!” attests. We’ll just conveniently ignore the fact that both Tannhäuser and Elisabeth are dead and Wolfram’s love was unrequited. This is opera, after all.

Lohengrin

Lohengrin received its premiere in Weimer in 1850, directed by Liszt. Wagner, tucked away in Switzerland to avoid the German police and their arrest warrant, was unable to attend.

The opera is in three acts with a shimmering prelude representing the Holy Grail. It takes place in 10th-century Antwerp, and opens on the banks of the River Scheldt. In a recent Bayreuth production, the chorus, which has a substantial role, was costumed as rats. No, that is not a typo. Check it out online; it looks like a bad community production of Nutcracker.

ACT I

King Heinrich is in Brabant to request help defending Germany from an Eastern invasion. A count of Brabant, Friedrich von Telramund, accuses Elsa of Brabant of murdering her brother Gottfried, heir to the Dukedom, which Telramund now claims for himself. He requests a judgment by combat. Just when it looks as if Elsa will be undefended, a knight (Lohengrin) appears in a boat drawn by a swan. He agrees to be her champion and marry her if she promises never to ask his name or origin. He then defeats Telramund handily; he’s a tenor, after all.

ACT II

Telramund and his witchy wife Ortrud spend most of the act thinking up ways to upset Elsa and make her worry about this total unknown she’s about to marry. They do a good job.

ACT III

This starts with a famous orchestral introduction, which the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra will kindly play for us. When the curtain rises, we see the bridal chamber. It is immediately after the wedding of Elsa and Lohengrin. Everyone (including us, the chorus) is offstage. We start singing offstage and enter halfway through our song, women on the right with Elsa, men (including King Heinrich) on the left with Lohengrin.

Treulich geführt ziehet dahin,

wo euch der Segen der Liebe bewahr’!

Siegreicher Mut, Minnegewinn

eint euch in Treue zum seligsten Paar.

Streiter der Tugend, schreite voran!

Zierde der Jugend, schreite voran!

Rauschen des Festes seid entronnen,

Wonne des Herzens sei euch gewonnen!

Duftender Raum, zur Liebe geschmückt,

nehm’ euch nun auf, dem Glanze entrückt.

Treulich geführt ziehet nun ein,

wo euch der Segen, der Liebe bewahr’!

Siegreicher Mut, Minne so rein

eint euch in Treue zum seligsten Paar.

Faithfully guided, draw near

to where the blessing of love will preserve you.

Triumphant courage, love’s reward

joins you in faith as the happiest of couples.

Champion of virtue, proceed!

Jewel of youth, proceed!

Flee now the splendid feast,

the joy of the heart be yours.

This fragrant room, decked for love,

now takes you in, away from the splendor.

Faithfully guided, draw near

to where the blessing of love will preserve you.

Triumphant courage, love so pure

joins you in faith as the happiest of couples.

The two groups meet in the middle of the stage, at which point eight of Elsa’s attendants sing:

Wie Gott euch selig weihte,

zu Freuden weihn euch wir.

In Liebesglücks Geleite

denkt lang der Stunde hier!

As God blessed you in happiness,

so do we bless you in joy.

Watched over by love’s happiness,

may you long remember this hour.

The King then embraces and blesses the couple, and pages give the signal to leave. We head offstage in opposite directions, women now to the left and men to the right, singing as we go:

Treulich bewacht bleibet zurück,

wo euch der Segen der Liebe bewahr’!

Siegreicher Mut, Minne und Glück

eint euch in Treue zum seligsten Paar.

Streiter der Tugend, bleibe daheim!

Zierde der Jugend, bleibe daheim!

Rauschen des Festes seid entronnen,

Wonne des Herzens sei euch gewonnen!

Duftender Raum, zur Liebe geschmückt,

nahm’ euch nun auf, dem Glanze entrückt.

Faithfully guided, remain behind

where the blessing of love will preserve you.

Triumphant courage, love and happiness

join you in faith as the happiest of couples.

Champion of virtue, remain here!

Jewel of youth, remain here!

Flee now the splendid feast,

the joy of the heart be yours.

This fragrant room, decked for love,

has taken you away from the splendor.

We’re now offstage, the doors are closed, and the audience hears our closing music only from the distance:

Treulich bewacht bleibet zurück,

wo euch der Segen der Liebe bewahr’!

Siegreicher Mut, Minne und Glück

eint euch in Treue zum seligsten Paar.

Faithfully guided, remain behind

where the blessing of love will preserve you.

Triumphant courage, love and happiness

join you in faith as the happiest of couples.

Elsa and Lohengrin are alone at last. Do they hop into bed and start fooling around? No, they do not. They fight. And sure enough, she asks him who he is. And just then Telramund and his men break in. Elsa gives Lohengrin his sword, he kills Telramund, and the bad guys all give up.

The final scene takes place back by the River Schedlt again, at daybreak. Lohengrin tells the king he must leave and says he is a Knight of the Holy Grail, who remains powerful only with anonymity. His name is Lohengrin, and his father is Parsifal. The swan and the boat reappear. Lohengrin frees the swan, who was bewitched by Ortrud and is Elsa’s lost brother. Lohengrin proclaims him Duke of Brabant and then departs. Elsa falls to the ground, lifeless. No one lives happily ever after. The End.

Really, this opera is maddening. The listener wants to throttle both Lohengrin and Elsa. It’s some consolation to think that if it had a modern-day setting, Elsa would have a law degree and would be able to forestall Telramund’s claims to the Duchy by an arcane series of legal delaying tactics. Or she’d be trained in the martial arts and be able to kick his ass herself.

But at least the music is gorgeous.

Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (The Mastersingers of Nuremberg)

The original mastersingers flourished from the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries, and were still in existence in the nineteenth century. These men (and they were all men) gathered to write and perform songs that followed very specific textual and musical rules, with the basic formal structure being “bar form,” AAB, or (in German) Stollen, Stollen Abgesang. The men were members of the bourgeoisie, and Wagner identifies his Meistersingers as cobbler, goldsmith, baker, tailor, and so on. The roots of their writing go back to the courtly “Minnesingers” of the Middle Ages (“minne” means “love” in Middle High German) whom Wagner celebrated in Tannhäuser, and, in fact, Die Meistersinger was originally intended as a kind of comic “appendage” to Tannhäuser (both are about song contests). As with that opera, Die Meistersinger inserts real people into the drama. All of the mastersingers in the opera were real, with the best-known being Hans Sachs (1494–1576), a shoemaker, who was famous for the quantity and quality of his songs. Wagner followed historical evidence in various places throughout the opera, e.g. mastersinger meetings typically took place after church services, songs were graded by “markers,” und so weiter. He made some switches, though. The Meistersingers of Nuremberg were in their heyday in the sixteenth century, when they numbered more than 250; Wagner cuts this down to 12. They met in St. Martha’s church, but Wagner thought that St. Catherine’s was a better venue and set it there (alas, it is now a bombed-out ruin).

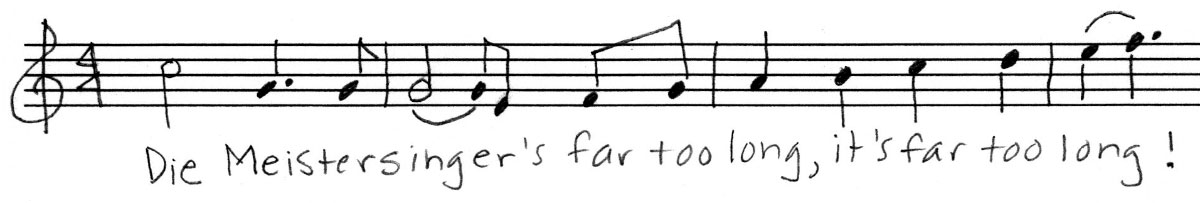

Wagner first sketched the opera in 1845 but it was many years before he returned to it. He took a break while writing his massive Ring cycle, pausing after the first draft of Act II of Siegfried. The intention was to toss off a couple of simple operas to cleanse his compositional palate and send him back to the Ring invigorated. But the two operas happened to be the massive and chromatic Tristan and Isolde, and the even more massive (but considerably less chromatic) Meistersinger. Music students, in fact, typically remember the (instrumental) opening to the opera by adding very appropriate words:

Wagner finished the libretto in January 1862 and the music in October 1867. The opera received its premiere in Munich on 21 June 1868, with the audience including Bruckner, Bavarian King Ludwig II (the opera’s dedicatee), the Wesendoncks (Wagner’s hots for Frau Wesendonck being the impetus behind Tristan und Isolde), Eduard Hanslick (the most important music critic of the time and an anti-Wagnerian; more on him below), the famed Russian writer Turgenev; and other luminaries. The work was a success, as it deserved to be. It’s got terrific music, it’s the only comic opera among Wagner’s mature works, there’s a happy ending, no one dies, etc.

The opera takes place in mid-sixteenth-century Nuremberg on June 23 and 24. It opens with an excellent “Prelude” that functions like an overture to a Broadway musical in its inclusion of the big tunes that will pepper the opera. The following plot summary is highly condensed, and leaves out all the parts where Hans Sachs is depicted as a wise soul and all-round good guy (Wagner self-identified with Sachs); he’s the one who believes in Walther and prevents the elopement.

ACT I

Interior of St. Catherine’s Church

During the concluding chorale of the church service, newcomer Walther von Stolzing (a Franconian knight) sees Eva, the daughter of goldsmith Veit Pogner. They rapidly fall in love (this is opera; there’s no time to waste), but Eva’s weird dad has promised her to the winner of the upcoming song contest. Although she’s allowed to turn the winner down (gosh, how considerate of her father!), he still requires her to marry a Meistersinger. Plus, the town clerk Sixtus Beckmesser is also in love with Eva. Walther wants to enter the contest, but he’s not particularly respectful of their rules of composition. In his preliminary trial held before the Meistersingers, Beckmesser is the marker and gives many, many bad marks to Walther, who is thus tagged as a bad singer.

ACT II

Street in Nuremberg, with both Sachs’s house and Pogner’s house

Eva and Walther meet again; they decide to elope. Beckmesser shows up to serenade “Eva” (who is actually Magdalena, the girlfriend of Sachs’s apprentice David, in disguise). Sachs “marks” errors in Beckmesser’s song with strokes from his shoemaker’s hammer. David thinks that Beckmesser is serenading Magdalena, and attacks him. Townspeople join the brawl; an uproar ensues; Sachs makes sure that Eva gets home safely and hides Walther in his shop.

ACT III

First part: Sachs’s shop

Walther tells Sachs of a wonderful melody that came to him in a dream; guided by Sachs on how to write something that is new but won’t scare the elders, he dictates the first parts of his Prize Song to Sachs. Both then leave. Beckmesser enters, finds the song, thinks it is by Sachs, and steals it. Sachs, entering, realizes that Beckmesser has stolen the song but lets him take it, promising Beckmesser that he (Sachs) will never claim the song as his own. Eva comes in with a shoe to be fixed; Walther returns with his finished song; they are joined by David and Magdalena, and, with Sachs, they sing the only quintet Wagner ever wrote.

Closing part: meadow on the banks of the river Pegnitz

The townspeople gather; after the entrance of the various guilds and the Meistersingers, we townspeople honor Sachs for being such a mensch by singing the chorale “Wach auf,” whose words are (for once) not by Wagner but rather (except for the coda) by the real Hans Sachs himself, from his Die wittenbergisch Nachtigall of 1523 (the nightingale is Martin Luther).

Wach auf! Es nahet gen den Tag

Ich hör singen im grünen Hag

ein’ wonnigliche Nachtigal

ihr’ Stimm’ durchdringet Berg und Thal

die Nacht neigt sich zum Occident

der Tag geht auf von Orient

die rothbrünstige Morgenröth’

her durch die trüben Wolken geht.

Ah! Nürnbergs theurem Sachs!

Heil Nürnbergs theurem Sachs!

Awake! The day draws near.

I hear singing in the green grove,

a blissful nightingale.

Its voice penetrates mountain and valley.

Night sinks in the West.

Day rises in the East.

The passion-red sunrise

goes hither through the turbid clouds

Ah! Nuremberg’s dear Sachs!

Hail, Nuremberg’s dear Sachs!

(Translation: Honey Meconi)

Sachs now opens the contest. Beckmesser tries to sing Walther’s song (thinking it is Sachs’s) but messes up badly. Then Walther sings it properly (the song now pays homage to the rules but departs from them as well) and wins the contest and Eva. Walther is supposed to join the Meistersingers but doesn’t want to, so Sachs convinces him by singing his defense of “holy German art,” with everyone joining in to conclude the opera. Rah Germany! (Sachs’s pro-German monologue did not sit well with everyone; in the decades following the opera’s premiere it was sometimes cut in foreign productions).

Die Meistersinger is obviously a transparent and self-serving allegory for Wagner’s own compositional path, where the (once-denigrated) creator triumphs in the end because he dares to take music in a new direction: art must continue to evolve and not be constricted by unnecessary reverence for rules. But the opera prompts some less innocent interpretations as well. Many commentators now view Wagner’s depiction of Beckmesser not as a playful poke at a sad pedant, but rather as an intentionally cruel anti-semitic portrait. The character of Beckmesser, after all, was at one time named “Veit Hanslich” after Eduard Hanslick, the important Viennese music critic who did not like Wagner or the “New German School” of composition (on the latter, see the discussion under the Franz Liszt entry). Hanslick was born and raised Catholic, but his mother had converted from Judaism on her marriage to Hanslick’s Catholic father, and that was enough for the anti-semite Wagner.

Some also see the opera as “the artistic component in Wagner’s ideological crusade of the 1860s: a crusade to revive the ‘German spirit’ and purge it of alien elements, chief among which were the Jews” (Barry Millington in the New Grove Opera Dictionary; he also describes it as “a glorious affirmation of humanity and the value of art, as well as a parable about the necessity of tempering the inspiration of genius with the rules of form”). German author Thomas Mann, whose writing was heavily influenced by Wagner, wrote in 1950 that “Meistersinger contains the most wonderful music, but it is not entirely coincidental that Hitler liked it so much.”

In connection with the idea of national purity, musicologist Pamela Potter observes that “The feeble attempts during the Third Reich to repopularize Wagner’s music had only limited success,” but she notes that Meistersinger was a special case; it became “the centerpiece of official ceremonies.” Scholars have documented various icky ways in which Nazi creeps turbocharged Wagner’s nationalism, thus tainting the opera ever after for some listeners. Curiously, though, Nazi Meistersinger productions never paid any attention to Beckmesser as a stand-in for the Jews.

Germany was not yet unified when Wagner wrote Die Meistersinger, and many other composers were engaged in nationalistic composition: Verdi, Dvořák, Sibelius, you name it. But the nations those composers were hoping to see established were not the ones who plunged the world into two horrific wars and eagerly planned the extermination of anyone they didn’t like (Jews, gays, disabled people, etc.) So Wagner’s encomium to German art can take on a sinister aspect, and modern stage directors do not shy away from confronting that. In the production I saw in 2019 (at Bayreuth no less!) the brawl at the end of Act II turned into a kind of mini-pogrom, and Act III was set in the same courtroom where the Nuremberg Trials for Nazi war criminals took place.

A Personal Note—Bayreuth

Hearing Wagner in Bayreuth has been a dream of mine ever since I learned of its existence as an undergraduate music major. In fact, though, I never expected to go there. There’s a multi-year waiting list for tickets, and I’m not exactly Angela Merkel (tickets are readily available for major figures in German life). In the summer of 2019, however, tickets to the festival fell into my lap at the last minute through a friend of a friend, and at the Finger Lakes Choral Festival concert that summer, as the orchestra played the Meistersinger Prelude, I could think blissfully “the next time I hear this I will be at Bayreuth!”

Aside from the tremendous good fortune of access to tickets, I was joining a friend of several decades’ standing, a friend from more recent years, and two brand-new friends, all of whom were Bayreuth veterans. They were thus able to act as superlative guides for all things Bayreuthian, from accommodations (a hotel with a massive breakfast buffet that kept one full until the early dinner required by Bayreuth’s 4:00 p.m. start times, plus a shuttle to and from the grounds) to clothes (an evening gown is not out of place) to the need for an genuine evening purse (no large bags allowed inside the Festspielhaus) and so on. One charming aspect of the performances is that there are fanfares shortly before each act from the balcony at the front of the Festspielhaus. Fifteen minutes before an act begins, there is a single fanfare; ten minutes before there’s a double fanfare; and five minutes before there’s a triple fanfare. The fanfares are always well-known melodies from the opera being performed.

Not surprisingly, there’s no admission to the hall after the act begins, and it’s both a solemn and exciting moment when they close the doors. My first opera was Parsifal, nicely symbolic since it is the only opera Wagner wrote specifically for Bayreuth, and for decades no one was allowed to perform it outside of Bayreuth. When the Prelude began, I started crying from the sheer emotion of being there, in Bayreuth, hearing Parsifal. As I wrote in my journal that night (three hours after I got back to my hotel room; I was too wired to sleep) “I truly never dreamed I would ever be watching Wagner at Bayreuth.” The other time I cried during my Bayreuth visit was when Elisabeth sings her aria “Dich teure Halle” at the beginning of Act II of Tannhäuser, since (aside from the Ride of the Valkyries) that was the first Wagner I ever learned, way back in my undergraduate days. And sitting in the darkened theater on other nights, I found myself thinking again and again “I am seeing Wagner in Bayreuth!”

Tristan und Isolde and Meistersinger were the two other operas I saw, and I had a different seat each night (I learned that one rents cushions to make the hard seats tolerable). It didn’t matter where I sat, though; sight lines were good pretty much everywhere and the acoustics were as marvelous as their reputation. Plus it’s wonderful being surrounded by a passionate, committed, and knowledgeable audience. The orchestra was fantastic, the singing was superb, and the productions were...well, interesting. I’m not sure anyone does “straight” Wagner anymore these days, and Bayreuth is at the forefront of innovative productions (which is not necessarily the same thing as good productions). But, hey! I was at Bayreuth!

There was also plenty to do during the daytime or on non-opera days. Wagner’s house Wahnfried is an excellent museum; his grave is in the back yard; his son Siegfried’s house and Liszt’s house are right there as well. Liszt and a batch of the Wagner family are buried in the cemetery; there’s the church where Bruckner played organ for Liszt’s funeral; and there’s an attractive Baroque opera house in town as well (which, to my mind, is practically begging for productions of Baroque opera, since there are nights when one is not at the Festspielhaus). I ate at a favorite restaurant of Wagner’s, I went to a wonderful piano recital (all Rossini!) one night at Wahnfried, Wagner’s house, and I took a day trip to Nuremberg to see the St. Martha’s and St. Catherine’s churches, the Hans Sachs statue, Albrecht Dürer’s house, the site of the synagogue (destroyed on Kristallnacht), and the courtroom for the Nuremberg Trials.

As you know from reading this Wagner entry, his anti-semitism and his posthumous championing by the Nazis are certainly black marks against his legacy. But now, in contrast to the past, Bayreuth is addressing rather than avoiding these facts, led by the current Festspielhaus director, Katharina Wagner (who is Wagner’s great-granddaughter and Liszt’s great-great-granddaughter). I’ve already noted the 2019 Meistersinger production, and in the 2007 Bayreuth production, staged by Katharina, Sachs is played as the villain who has an unhealthy influence over Walther and das Volk. The Siegfried Wagner house is filled with displays that acknowledge the enthusiastic (and sickening) welcome the family accorded Hitler and his thugs, and the beautiful grounds of the Festspielhaus include a prominent display called “Disappeared Voices” that identifies Jewish musicians connected to Bayreuth and indicates what became of them—needless to say, a very sad and moving exhibit. I suspect that almost every visitor to Bayreuth sees it, for the intervals are very long and one can only stand in line for bratwurst or ice cream so many times.

But it is worth ending this on a more cheerful note, ergo: I flew into and out of Munich on my trip, and while there I stopped by the statue of Renaissance composer Orlande de Lassus, who worked for the Bavarian court for many years. To my surprise, I discovered that, although Lassus is the persona of the statue, the base has been turned into a shrine to Michael Jackson—who knew?

November 2015; Revised July 2017, November 2021

![]()